Brohm family ties run deep in Louisville, especially in athletics.

They are what makes them the "First Family" of Louisville, according to a family friend. And that deep-rooted history makes Purdue's opener vs. Louisville Sept. 2 in Indianapolis even more special for many.

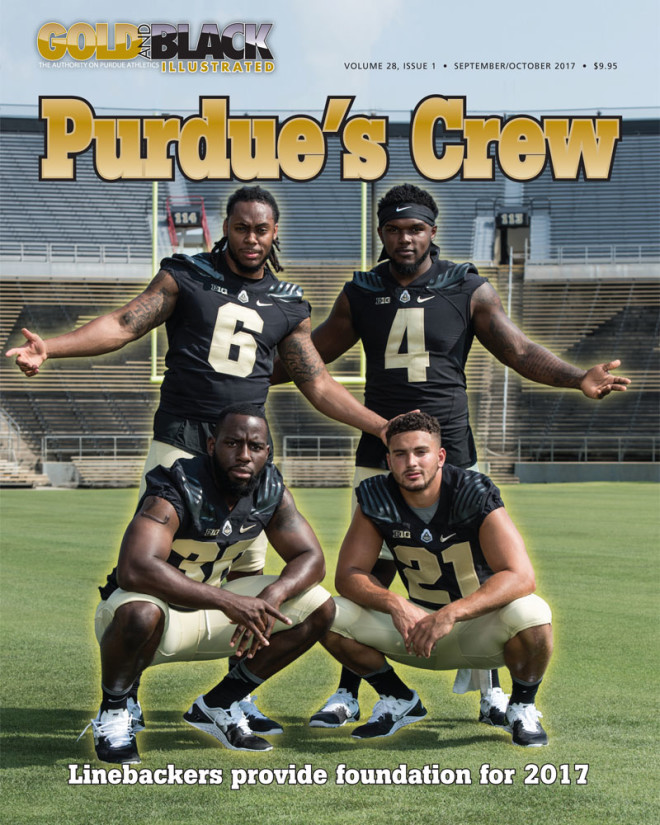

Below is the cover story in the Gold and Black Illustrated, Vol 28, Issue 1, outlining those family ties. (Scroll down to read. Or for the magazine version of the story — in PDF form — click HERE).

For a special price of $8.95 (and free shipping), order the magazine now by clicking RIGHT HERE or on the cover above. In the September/October edition, you'll find the feature on the Brohms' history in Louisville, news from Purdue's training camp, a projected depth chart and features on Da'Wan Hunte and the legacy of Bob DeMoss, along with a men's basketball summer update and previews of volleyball and soccer.

The 'First Family' Of Louisville

They’d look up in the stands and, naturally, see a bunch of family members.

Father Oscar, mom Donna, sister Kim, brother Brian clad in blood red.

Grandparents, uncles, aunts and cousins, too.

But then they’d notice a neighbor, smiling widely after a big play.

They’d notice a grocery store clerk from down the street, a waiter from their favorite restaurant, a fellow church parishioner.

Seemingly, the whole football stadium, as it were — really, it was a rundown baseball stadium in the 1980s but still home for a revitalized Louisville football program with Jeff Brohm leading the show at quarterback and older brother Greg flashing talent at wide receiver — was full of more than fans.

The Louisville community so embraced the Brohm family — first Oscar, an all-state high school quarterback at powerhouse Flaget High School before moving on to quarterback U of L, then his son Greg starting the Trinity wave that moved to Jeff and youngest Brian — that the people who were full-throated yelling with every touchdown throw, every catch, every victory may as well have been related.

Really, the Brohms kind of saw it that way anyway.

“My mom, my dad, they had big families, so everybody kind of knew us growing up,” Greg Brohm said. “We were part of the community. That means as much as anything because I think even though we had fans in the stands, it felt like we had friends in the stands when they were watching us. They weren’t just fans of the team, they were our friends. You thought they had your back, even if you didn’t play well. You thought they would back you.”

Maybe that won’t exactly be the makeup in the stands on Sept. 2 at Lucas Oil Stadium.

There definitely will be a horde of folks clad in Louisville red, donning gear with the menacing, teeth-gritted Cardinal logo, perched on their seats for every ooh-and-ahh-inducing move Heisman-winning quarterback Lamar Jackson pulls.

But the opponent in that season-opening, primetime game is Purdue.

And it’s on those sidelines where the sons of Louisville’s past will be.

Red now is the color the Brohms can’t be caught wearing. Not with how deeply the rivalry with Indiana runs.

But they’re still the same guys, the good-natured, down-to-earth Brohm boys, reputation earned not just for their athletic prowess growing up in the Highview/Fern Creek neighborhood but for their character and humility.

Whether those Louisville fans let slip a hard clap if David Blough, under the direction of quarterback coach Brian Brohm, throws a TD pass after a masterful play call by Jeff Brohm with chief of staff Greg Brohm watching from the sidelines — and, probably, Oscar, too, assuming he can snag a field pass — could be the real storyline.

It’ll likely happen.

It has to.

What with how much that family means to the city.

“In Louisville, their name is synonymous with football. They are the first family of football in Louisville. No doubt about it,” said Shawn Freibert, who grew up in Louisville and is a friend of the family.

“Around these parts, that name means everything. … Their whole family has always been just terrific people, involved with the game and in all sports. They’re a very athletic family.”

Oscar Brohm had a choice.

He was the oldest of nine kids to Oscar Sr. and Frances, and his dad never played football, other than tossing the ball around with his sons. But everybody in the Shively/St. Denis neighborhood of Louisville played some kind of ball — basketball, baseball, football — and as a naturally gifted athlete, Oscar Jr. was drawn in.

He started playing organized football in sixth grade and quickly made a name for himself as an impressive athlete in the city at Flaget High School, a prestigious Catholic school that boasts Howard Schnellenberger and Paul Hornung as alumni. Oscar was a strong-armed, savvy quarterback who walked into the perfect situation: An offense that passed the ball, a rarity in the 1960s, he said.

So he slung it around every week, and, by the time he left the school, he held the city’s single-season passing record with 23 touchdowns over an 11-game season as a senior. It was a record that stood for about 30 years until Chris Redman broke it. He threw for 1,848 yards that season and led Flaget to the Louisville city championship and a runner-up finish at state.

He was a first-team AP all-state quarterback that year, too, flashing a No. 11 jersey that became quite a special one at the school. Before him, Rick Norton wore it and was an all-state quarterback before becoming an All-American at Kentucky and playing in the NFL for the Dolphins. After him, John McGrath wore it and continued the tradition, being named an all-state quarterback and, ultimately, earning Kentucky High School Athlete-of-the-Year in 1972.

For McGrath, there was no doubt which number he wanted to wear at Flaget.

And there was one reason: Because Oscar had donned it.

McGrath was six years younger than Oscar, but he was around him all the time growing up. The McGraths and Brohms all went to St. Denis Elementary School. Most of them followed the same path to Flaget, until it closed in 1974.

McGrath’s father, Joe, coached Oscar in everything: Baseball, basketball and football. And little John was so obsessed with sports — his dad played football and basketball at Louisville before locking in as a local youth coach for 44 years — he always was the water boy, the ball boy, intent on the sidelines or dugout watching Oscar’s every move.

“He was probably the best athlete in Louisville when he was young,” said John McGrath, who was given rides to high school from Oscar’s siblings. “He was a great pitcher, a great basketball player, a quarterback. He played all those sports at Flaget. It was just natural, since I always was around the team and my dad was coaching and he was the star player, I looked up to him. He was my idol growing up.

“You would think talking to Oscar, he’s just a normal guy. He is just a great person.”

So with Oscar, it all started.

“The Brohm name meant a lot when (Oscar) was a celebrity athlete,” Schnellenberger said.

The legacy grew as Oscar’s brothers came through the ranks and all played football collegiately. Frank was a quarterback at Flaget before going to Eastern Kentucky; Dennis was a quarterback and running back for Flaget before playing at Dayton; Mike continued the QB tradition at a different high school in the area, Bishop David, before playing for two years at Western Kentucky; twins Donnie and Ronnie were a quarterback-receiver combination — there’d be another Brohm one to come — at DeSales High School in the late 70s before heading to the University of Louisville.

Donnie and Ronnie helped DeSales beat rising football power Trinity — a highlight of their career — while brother Dennis was coaching there.

“They were pretty good,” Oscar said of his brothers. “So they kept it going.”

The family’s legacy grew within the neighborhood every November.

That’s when all the Brohm boys and seemingly all their buddies smashed into the backyard of the Brohm house on Deveron Drive for what they dubbed the “Turkey Bowl.” The McGraths lived on the street behind Deveron, Thistledawn, so John and his brothers made sure to pop over and participate.

Oscar’s dad would hop onto the roof and film the games.

They were brutal, bloody and intense games of tackle football — hard to be much else considering the dimensions of the yard were 20 by, maybe, 15 feet. It was literally five guys lined up shoulder to shoulder on the “line” grinding ahead with a ballcarrier behind.

It was serious, too. There was an MVP trophy and, of course, bragging rights — and endless stories regaling and exaggerating moments, plays and, yes, injuries and fights.

One year, Oscar was forced to the hospital with three broken ribs and a collapsed lung. Apparently, there’s still a debate that rages today on whether he was injured on a dirty play. (The culprit, by the way, was one of his own brothers.)

Afterward, all would huddle into the Brohm house, pull out the reel-to-reel and watch games from previous years.

One year, there were as many as eight college football players playing in the game, McGrath said.

“We’d all come back (from college), we’d eat Thanksgiving dinner and we’d go straight to the Brohms’ house,” McGrath said of the tradition that started in the 1970s. “It went back so many years that I can remember one year Jeff and Greg were holding the sticks — they utilized brooms and whatever — and had the downmarkers on the brooms. So it was really, really a tradition that we looked forward to every year. As we got older, we had to give it up.”

Part of that was because of the physical toll the game took.

Another factor: Their attention was diverted to raising their own families.

Greg and Jeff Brohm had little choice.

As the sons of Oscar and Donna, who was an elite athlete pre-Title IX in the 1960s and may be the most competitive of the bunch, and the nephews of six sport-enthusiast uncles, oldest son Greg and Jeff, one year younger, were enlisted into youth leagues in multiple sports ASAP.

Even before they started organized football, Oscar had them in the backyard preparing arms, hands and feet.

Greg isn’t quite sure why, as the oldest, he wasn’t groomed to be the QB — and, really, Oscar says he’s not sure either, admitting Greg has “a really good throwing motion” — but Jeff earned that label as a youngster, and Greg landed at receiver.

They started in flag football and made an impression early: While the other teams in the league were handing off, their team, coached by Oscar, was chucking 20 passes a game. Most kids that young can’t throw and catch well, let alone consistently.

“They could,” Oscar said. “In first grade, they could throw and they could catch. ”

As 8- and 7-year-old kids, Greg and Jeff played in the Fern Creek youth leagues, baseball in the summer, coached by their dad, and basketball in the winter, coached by their dad.

“They were good at all of them. They excelled at everything,” McGrath said. “So there was a big buzz.”

Considering the talent level of the boys, choosing which Catholic high school to attend was a big decision. One of the school powers was going to get a lot more potent.

By the time Greg chose to attend Trinity High School in the mid-1980s, essentially lining up Jeff to do the same, the community was ready to embrace them.

“People who knew football highly anticipated the arrival of the Brohms,” said longtime sportswriter Rick Bozich, who started covering sports in the Louisville area in 1978.

Even if the Brohms themselves didn’t quite feel the buzz.

In their first couple years, they had to take the local TARC bus transit three times to get to and from school, which was 25 minutes away from their house.

“We were nobodies. Trust me,” Jeff said. “Once we got older, we got a ride in the car. Early on, it was like, ‘Geez.’ We had to earn our stripes.”

There’s little doubt they did just that.

Both Greg and Jeff were three-sport stars, playing basketball, baseball and football. Greg was a point guard and all-district baseball player. Jeff was the basketball team’s leading scorer and assist man as a senior, earning MVP honors, and developed into a pro baseball prospect. As a senior, Jeff had 23 scouts show up for a Babe Ruth League game, Oscar said, and in the days leading into that year’s Major League Baseball draft, Oscar was being told by a handful of scouts they’d take Jeff in the first round if he opted not to play football.

But how could Jeff not play football?

At Trinity, Jeff showcased his elite athleticism at quarterback weekly, essentially as a runner who could throw — “If you ever watch some of his high school film, it’s some of the best scrambling and improvisation you’ve ever seen,” Greg said of his brother, who reportedly had sub-4.4 speed — and Greg often was a significant beneficiary of Jeff’s passing talent. By Greg’s senior year, he was a first-team all-state receiver.

By Jeff’s senior year, he’d become one of the state’s best players, leading Trinity to an undefeated season, capped by a Class 4A state title after throwing for 1,707 yards and 20 touchdowns and rushing for 602 yards and 12 TDs to earn Mr. Football in 1988.

“He’s special,” former Trinity football coach Dennis Lampley said. “He could have been a coach in anything. In any sport, football, basketball, baseball, the whole works. He knew it all. He studied it. He worked at it. He hustled. There was no laying down, not going as hard as you can go. He could always do that.

“All the Brohms could. They’re almost clones, the way their attitudes are, the way they work.”

That kind of senior season had college football coaches drooling.

Notre Dame, Boston College and USC wanted Jeff. So did Louisville, a program that only a handful of years earlier considered de-emphasizing football and dropping from then-Division I-A to I-AA.

Jeff couldn’t possibly stay home, could he? Not with iconic Catholic school Notre Dame and legendary coach Lou Holtz calling? But the Irish also had a freshman quarterback named Rick Mirer.

Louisville had Howard Schnellenberger. And Greg Brohm.

“To me, the shrewdest move Howard Schnellenberger made was taking Greg,” Bozich said. “Greg was, in retrospect, good enough to play at Louisville but very few people thought he was good enough to play at a high level (initially). By getting Greg, I think that helped them get Jeff. They’re very close. They’ve always been very close.”

Schnellenberger, the ultimate salesman and big talker, already had a Brohm connection. He was a Flaget graduate who knew Oscar and already had a reputation for developing quarterbacks. He already had won a national championship, as the head coach at Miami in 1983. He already had won a Super Bowl championship, as an assistant coach on the Dolphins’ undefeated 1972 team, and, thus, had a firm grasp on what it took to prepare a player for the NFL.

It didn’t hurt that on Jeff’s recruiting visit, Schnellenberger had the group of other prospects eat dinner at one restaurant while he took Jeff to another, Pat’s, the best steakhouse in town. Because, as Schnellenberger said, “I take all my quarterbacks out, but I don’t take them out with ordinary people. The quarterbacks get preferential treatment.”

Jeff certainly felt special.

“He sold me on, ‘Hey, you can go somewhere else and be a normal guy or you could come here and be a difference-maker.’ So I said, ‘Hey, let’s try to do it here in my backyard. I’ll be a difference-maker,’ and it paid off for me,” Jeff said. “You can go to any school and accomplish what you need to, but it needs to be a fit, and I thought that Louisville fit me and it was beneficial for me.”

The city was ecstatic to keep a homegrown golden boy in its backyard.

And that includes Jeff’s childhood friend, Freibert, who often rode to high school with Jeff. Freibert said he’ll never forget the particular morning commute when Jeff told him he was going to Louisville.

“I was like, ‘Are you serious?’ Everybody was after him. It was a neat deal. I’m like, ‘I won’t say a word, man.’ But I was so happy,” Freibert said. “I grew up a Louisville fan, and I didn’t think there was a prayer he was going to Louisville, no matter what Schnellenberger had said. He put a lot of pressure on him.

“At the time, Louisville football wasn’t what it is today. I shouldn’t say I didn’t think they had a chance — being at home and his family, I knew all that was important to him. But when every school in the country is after you …”

And that decision just may have changed the course of Louisville football, people familiar with the program said.

Schnellenberger worked through lean years in his first several in the program — 2-9, 3-8, 3-7-1 seasons — but when he landed Jeff, that’s when the “meteoric rise” started, he said.

“We had made progress. (But they were) hard, hard struggles, hard to swallow,” Schnellenberger said. “But we had to go through those first three years. Then Jeff was in the next set of players, and it gave us the firepower, the strength of the team, the depth of the team, when he became part of it. To have his brother to throw to and his daddy to throw to them in the backyard on Sunday and then Jeff as a quarterback, Greg was his brother, Jeff knew him so well, he would just throw the ball to a spot and Greg would amble over there and catch it.

“We had some great years there. That brother combination quarterback-to-receiver was highly important in our success.”

Greg, who had 45 career catches for 722 yards and four TDs, saw the transformation of the program first-hand. He said he had an idea that it was a rebuilding project when he signed on, but he also believed every word Schnellenberger said: He believed it’d develop into a prominent program.

In Greg’s first season in 1988, Louisville won eight games. In 1989, it was 6-5. Then, in 1990, came the breakthrough, going 10-1-1 and beating Alabama in the Fiesta Bowl.

In Jeff’s two seasons as starting quarterback in 1992 and 1993, Louisville was 5-6 and 9-3. His final game was a victory over Michigan State in the Liberty Bowl. That capped quite a career as he left the school among its all-time leaders in passing yards, touchdown passes, completions, attempts and completion percentage. (He’s still top 10 all-time in all of them.)

He was a two-time team MVP as well as MVP in that final bowl game, which simply playing in was a considerable accomplishment: He had a steel plate and pins in the index finger on his throwing hand and still passed for nearly 200 yards and a touchdown in freezing rain.

“I remember how good Jeff was and when I heard he didn’t go to Notre Dame and he went Louisville, I thought he was crazy,” Bozich said. “How could you turn down being the quarterback at Notre Dame to play at Louisville? In retrospect, he did the right thing. He played where he wanted to play. He played in front of his family and friends.

“Jeff made an imprint on Louisville football where he’ll always be remembered for what his contributions were there. (He) was one piece but a very important piece to kind of help change the dynamic of Louisville football. I think he made it acceptable for other (local) kids, like Chris Redman who followed him and Michael Bush and Brian, to say, ‘You don’t have to go to Notre Dame like Paul Hornung did.’ Or ‘You don’t have to go to Ohio State or Michigan or Kentucky. You can play at Louisville.’”

Even if you’re the son of a popular, successful local athlete and coach.

As the youngest soon learned.

“I think there was pressure on them,” Oscar said. “I think then when Jeff played, everybody had high expectations, and he was all-everything. Greg, too. So they had pressure on them. Then Brian came along and everybody was anticipating him. Brian had tremendous pressure on him. I don’t think there’s anywhere you couldn’t feel it. When you’re in the eighth grade and everybody is already talking about you ... Hey, when the whole city is pretty much putting pressure on you, that’s a lot of pressure.”

Brian Brohm had no choice.

Before he ever even stepped on a field, a diamond, a court, people had expectations. He always knew it, even as a kid. And he always felt like he had to fulfill them, lofty as they were.

He’d heard people say he’d be the best of the Brohm bunch.

And everyone in his family seemed to have the same mission: To build him into just that.

By the time Brian was playing flag football as a fourth-grader, it wasn’t just about throwing the ball, like Jeff and Greg had started with their team nearly 15 years earlier. It was much deeper than that. Brian’s uncle Donnie would tape the games and the next day, most of the family would watch the tape.

And critique it.

Flag football.

But it wasn’t just like that in football, though that was the most magnified, maybe, because of Brian’s talent and ceiling — and the family’s pedigree at quarterback.

Brian remembers one specific time when he scored 33 points in a basketball game, thought he played pretty well. But when they pulled into the driveway back home, it took three hours to make it inside the house. Oscar, Greg, Jeff and Brian picked up a ball and played a bit while the three oldest lectured the youngest on every little thing they thought Brian could have done differently, done better.

They’d offer the occasional “good job,” but it nearly always was followed with something he could improve. That was generally how it went. In youth leagues, in middle school, in high school, in college. Work always was being done, whether it was watching film, having special gatherings in the backyard to “train” for a season or to fix a throwing motion that felt out of whack — Donna usually was the one who filmed those sessions, and the whole family went inside to watch the footage before returning outdoors to initiate tweaks — or, simply, talking. That knowledge may not always have been welcomed by Brian, but ultimately he soaked it up. There was too much wisdom not to absorb every word, every idea, every critique.

“We talked ball a lot in our house,” said Brian, smiling. “I basically grew up with three coaches, Greg, Jeff and Oscar. There were multiple times they’d come to the games and watch, Greg and Jeff, my dad would be the coach and then you’d come home and you had three coaches reviewing the game and going over everything that happened during the game, what I could have done better.

“I was well-schooled growing up. I definitely had an advantage over the other kids who were playing. In all sports. It wasn’t just football. It was in everything.”

And, like his brothers, he excelled in all of them.

At Trinity, Brian was a star.

He was a Major League Baseball prospect — ultimately getting drafted by the Rockies in 2002. He was an MVP in basketball. And, in football, he thrived in Bob Beatty’s sophisticated offense that showcased a college-type passing game, allowing Brian to pile up ridiculous career statistics (10,579 yards, 119 TDs, only 14 interceptions), win three state championships and be named Kentucky’s Mr. Football as a senior. Now, his No. 12 jersey hangs on a wall inside the R.W. Marshall Sports Center, one of only three to be honored by a school that has won 24 state titles. Jeff’s No. 11 is nearby.

Brian’s ability — and willingness — to be a three-sport guy even landed him on the cover of Sports Illustrated as part of dying breed of high school athlete: One who doesn’t specialize.

But he’d have to in college.

And, with that decision, Brian could have escaped the expectations, the pressure and the family.

He was one of the country’s most-prized football prospects, being heavily recruited to play quarterback across the country. But his hometown school wanted him, too. The place where Oscar played. Where Greg and Jeff played. That had a resurgent program, a newer stadium, a growing fanbase and an offensive-minded coach and quarterback developer in Bobby Petrino. And Jeff as an offensive assistant coach.

“Did I want to stay and live with the pressure of the high expectations or did I want to go somewhere and start fresh and make a name for myself?” Brian said. “I decided to stay home and had a great career. I enjoyed every minute of it.”

Brian had one of the most successful careers in Louisville history, throwing for nearly 11,000 yards and 71 touchdowns, completing nearly 800 passes, winning 24 games and beating three ranked teams.

Decision validated.

“Everybody expected him to be great, and he lived up to it,” Greg said. “Every stage he was on, he was better than the stage he was on. He was always real calm and composed. The lights were never too bright for him. He couldn’t have done, really, any more in his athletic career in high school and in college. For somebody to have that much attention, he handled it great.”

Brian was selected in the second round of the NFL Draft. He spent eight seasons in professional football, including non-NFL stops, before retiring two years ago and joining Jeff’s staff last season at Western Kentucky. Which promptly had a first-time starting QB throw for more than 4,000 yards.

“I’ve kind of watched it all develop,” said Bozich, who worked alongside Oscar starting in the late 1970s. “When I first got to town and heard about Oscar’s kids and then to watch them actually … everybody says their kid is good. Yeah, I’ve heard that before. They might be good in grade school. Then they’re at Trinity and they’re winning state championships and they’re going to U of L. I remember hearing, ‘Brian is going to be better than either of them’ (and thinking), ‘Oh sure.’ Then Brian is better than either of them.

“All the hype — and they had plenty of hype — has been justified.”

Oscar Brohm holds the word out, for effect.

“Nooooo question,” he says when asked who he’ll be rooting for on Sept. 2 when his alma mater is pitted against the current employer of his three sons. “There’s no divided loyalty at all. Family first. I’ll even be trying to convert some of my U of L friends to pull for Purdue this game. Actually, I have, but I can’t give their names or they’d get in trouble.

“We’re real excited.”

He says this with a Purdue hat firmly on his head, discussing his family and its Louisville connections over lunch this summer at a restaurant just across the Kentucky border, peeking onto the Ohio River. He’s a chatty, personable storyteller and has just enough southern drawl to make every word interesting.

Around these parts, he’s simply known as “Oscar” now, no last name. When he’s out, either by himself or with Donna, often he’s stopped. Many ask about the boys.

It’s widely known they’re all up north now, having traded in their red for black and gold. And it’s widely known which team they’ll open with in Jeff’s first game as head coach. That’s probably more because it’s their beloved Cardinals, of course. But it just as easily could be because the careers of Jeff, Greg and Brian have been watched closely.

“Everybody around here, they know them. It’s nice that it’s that way,” Oscar said. “They used to be my sons and now I’m their dad, which is great. I love it.

“I feel lucky. Because what guy who was a former player wouldn’t enjoy being involved in it for his whole life with your sons and your daughter? It’s great. It keeps me young. I think it keeps me young.”

A pause, a smile.

Clearly, Oscar is enjoying every moment of this new experience, this fresh start, this introduction to a new community, he hopes, will embrace his family like the old one.

And he knows he’s not the only one relishing the possibilities.

When Greg was in the Louisville area this summer, he felt a buzz. He thinks that’ll carry into Lucas Oil Stadium, too, giving it a unique vibe.

“It’s going to be fun,” Greg said. “All our friends and family are going to be at the game. Only our family is probably rooting (for us) — maybe a few friends — they’re rooting for the other team this game. But they want us to do well. I think it’s going to be a great atmosphere. We always love playing in front of our — those — fans and those people.

“It’s going to be just like a family reunion.”

Though Jeff publicly hasn’t said much about the emotions he’ll have entering the game, there’s little doubt his pulse will be revved up.

He’ll be coaching against Bobby Petrino, a mentor whom he coached alongside at Louisville while Brian was the quarterback. Lucas Oil Stadium likely will be packed with fans who know him, personally or by reputation. And he knows this will be a prime opportunity to showcase his new program — and what it’s about — in front of that group.

“I think we’ve got a lot of supporters for our family and they understand what we’ve been able to do at the University of Louisville, and we take a lot of pride — we’re University of Louisville fans — but, without question, I think we can convert some,” Jeff said at a fan event in southern Indiana, just north of Louisville, earlier this summer. “I think we’ll get a very good backing from the area. I think they’ll be into the games. While they might not cheer for us as much as I would like the first game, you never know what could happen.”

An excited utterance.

A shy smile after a masterfully executed trick play.

A quick pop out of the seat after a big hit.

It’s the Brohms, after all. And Louisville folks can’t not root for them.

“The Brohm family in Louisville means great athletes, smart people and good people,” said McGrath, the family friend who grew up with Oscar, has four season tickets for Louisville and is a Kentucky grad. “Not only were they great athletes, but they’re of the finest quality people. People you’d love to have your kid coached by or be like. When people around here talk about the Brohms, they say, ‘Man, they were great athletes, but they were better people.’ ”

For Your Consideration

Oscar Brohm was nervous.

As a sixth-grader, daughter Kim came to him and declared she wanted to play football in a local Catholic league. It was tackle. With boys. She’d played “touch” football at recess in middle school with the boys all the time. Apparently, she was ready for the next step.

Oscar didn’t want her to play, but he didn’t necessarily tell her that either.

Fortunately, not just for him, she changed her mind.

“Word got around, she had said something to somebody and the guy who ran the league goes, ‘You’re not going to do that to me, are you?’” said Oscar, with a smile.

Kim’s plate was plenty full without football.

And though they may not have been the same sports her brothers played, she made just as much of an impression.

“Kim might be the best athlete in the group,” said longtime sports reporter Rick Bozich, who got to know the family well while covering the Louisville sports scene.

Ditto, says family friend Shawn Freibert, who grew up with Kim’s older brothers Jeff and Greg and is now Jeff’s agent.

“(Kim) might have been as athletic as any of them,” Freibert said.

Not only was she a three-sport athlete in high school at Mercy, an all-girls Catholic school in Louisville — playing either small forward or post in basketball, as a middle hitter in volleyball and middle infielder in softball — she surprisingly, and impressively, played three in college, too, at Spalding University in Louisville. She was the league MVP in softball at Spalding where she was coached by both parents for a couple years, which was nothing new, really. Like with his boys, Oscar made time to be active in Kim’s athletic pursuits, starting with coaching her in basketball and T-ball as a kid, and mom Donna passed along her considerable softball acumen.

“Kim was really good,” Oscar said. “I’m coaching her in T-ball, and one of the moms got really mad at me, saying I was favoring the boys. This was boys and girls. I said, ‘I try not to.’ I said, ‘You know our first baseman?’ She says, ‘Yeah, yeah, you favor him.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s not a boy.’ She didn’t look like a boy.

“Kim was probably our best player. I go, ‘That’s my daughter playing first base.’ She went, ‘Oh.’”

In an unofficial poll of sorts, Kim, Greg and youngest sibling Brian were asked who the best athlete in the family was. Right after Greg said, “every one of us would say ourselves,” he shifted gears.

“Somebody who doesn’t get a lot of credit is my sister, Kim. She played three sports in college, which is unusual,” he said. “I’m going to say Kim.”

Membership Info: Sign up for GoldandBlack.com now | Why join? | Questions?

Follow GoldandBlack.com: Twitter | Facebook

More: Gold and Black Illustrated/Gold and Black Express | Subscribe to our podcast

Copyright, Boilers, Inc. 2017. All Rights Reserved. Reproducing or using editorial or graphical content, in whole or in part, without permission, is strictly prohibited.